Before the coronavirus crisis, Saudi Arabia had bold plans to attract tourists from around the world with new-build cultural resorts and futuristic cities. Marisa Cannon asks what next?

Uber, Tesla and Softbank have been among some of the lucky beneficiaries of Saudi Arabia’s whopping US$320 billion sovereign wealth fund, which, in the early days of the pandemic, acted as a cash-rich saviour to floundering companies in which it saw potential.

These acquisitions, which include stakes in Newcastle United, cruise operator Carnival, Equinor and Live Nation, were strategic purchases for Saudi Arabia’s “Vision 2030” plan, which sets out to reduce the country’s reliance on oil by investing in sectors such as health, education, recreation and infrastructure.

Tourism is one area of the Vision – spearheaded by the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – in which the country has planned to invest heavily.

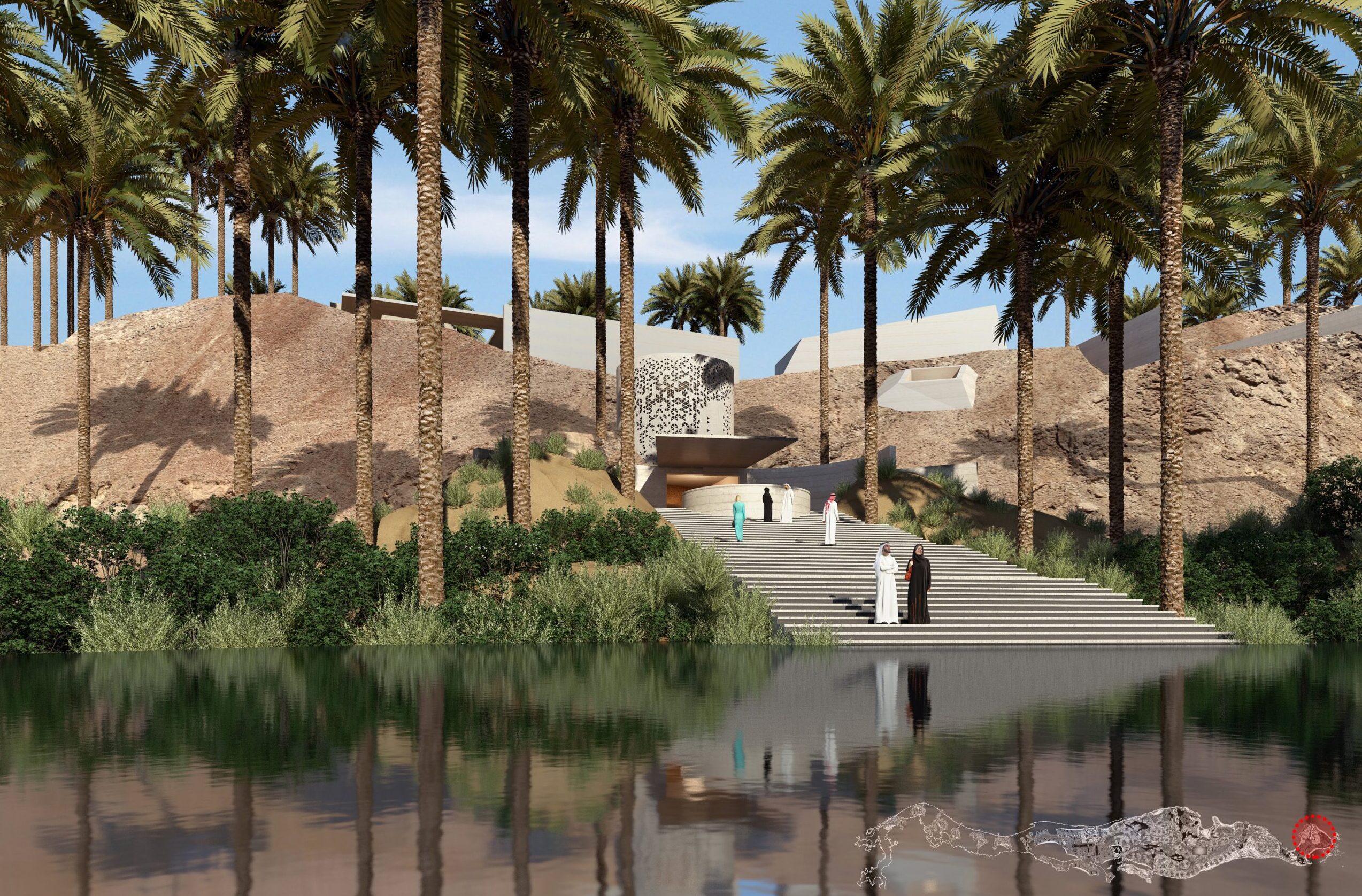

Developments include a series of luxury resorts across its Red Sea coastline, featuring 14 hotels with 3,000 rooms, restaurants, nature reserves and a US$500 million megacity that will cover an area 33 times the size of New York City.

Hailed “the world’s most ambitious project” by Saudi officials, the futuristic city of Neom has been pitted as an ultra-luxe combination of coastal paradise and tech utopia, where climate control technology, flying taxis and facial recognition are ubiquitous and school lessons are taught by holographic teachers.

Another project is Amaala Island, which has set its sights on becoming the “Riviera of the Middle East”, complete with wellness retreats, botanical gardens, galleries and state-of-the-art yachting and diving facilities. Vision 2030 had been banking on oil sales to fund these projects, but plateauing demand brought on by innovation in green tech and competition from American shale frackers, has begun to pose a real threat.

Vision 2030 had been banking on oil sales to fund these projects, but plateauing demand brought on by innovation in green tech and competition from American shale frackers, has begun to pose a real threat.

And now as a global recession looms into view, tanking oil prices, which have seen Saudi Aramco’s (the state oil company) first quarter profits fall by 25 per cent compared with last year, may well sound the Vision’s death knell.

As it stands, the government has announced a reduction of US$8 billion from the current blueprint, which serves as part of a wider US$27 billion austerity programme to shore up the kingdom’s contracting economy. This will include a trebling of VAT from five to 15 per cent on goods and services from July 1, and a suspension of the monthly cost-of-living allowance enjoyed by 1.5 million government workers.

At current spending levels and oil sales, Saudi Arabia may well run out of money within the next five years, says Karen Young, a Gulf analyst at the American Enterprise Institute who was quoted in The New York Times, driving it to take on more debt. This, coupled with IMF projections that the economy is on course to shrink by 2.3 per cent this year, present a gloomy picture for bin Salman’s diversification plans.

While the prince has kept tight-lipped about the Vision’s future, delays, at the very least, are certain. A Neom contractor is reported to have halved the working hours of staff, while an advisor on the destination’s board has said that the project would now be “stretched out over a longer period”.

But to others, the outlook is even dimmer. “I think Vision 2030 is more or less over,” says Michael Stephens (also in The New York Times), a Middle East analyst at the Royal United Services Institute. “Saudi Arabia is facing the hardest time it’s ever been through,” he added, “certainly the most difficult period of Mohammed bin Salman’s tenure.”

What’s coming next? Trend reports available to download HERE