Private jets have a reputation for being particularly bad for the environment but on-demand charter broker Victor is offering passengers the chance to invest in ‘sustainable aviation fuel’ (SAF) as a way of lessening their carbon footprint. Jenny Southan investigates

As a travel journalist, I get to go on some really interesting assignments from time to time. A few months ago I was invited to fly to Rotterdam on a private jet – they even threw in Tesla car transfers to Biggin Hill airport outside of London. It sounds glamorous – and the journey certainly was. No queues at the airport, just straight on to the tarmac and a short walk to our awaiting plane. We were served a quick breakfast before take-off, which was then cleared away because the G-force sends loose items flying during the ascent, and then we were up above the clouds. But instead of whizzing off to a Michelin-star restaurant, my fellow writers and I were to be taken to a factory to learn about how Finnish oil refining company Neste is developing a more environmentally friendly alternative to fossil fuel. Is it possible to fly guilt-free? Not yet but Victor is making efforts to reduce “carbon anxiety” and the negative impact of flying by filling planes with “sustainable aviation fuel” (also known as SAF) from products such as used cooking oil and animal fat. Walking around the outdoor refinery was a strange experience – we had to wear head-to-toe protective gear including helmets, goggles and earplugs. In fact the health and safety was so rigorous we had to send our clothing and shoe sizes in advance so we could be kitted out with the right-sized boots, trousers and jackets. Most sinister were the carbon monoxide detectors we had to wear in case of emergency. The idea of there being a gas leak or this place exploding suddenly felt like a very real risk. The sprawling structure took the form of a dystopian hissing exoskeleton with a tangle of pipes and imposing tanks. A nearby coal factory belched black smoke into the air. Was it possible that this place was creating a product so revolutionary it could transform the carbon impact of flying?

Is it possible to fly guilt-free? Not yet but Victor is making efforts to reduce “carbon anxiety” and the negative impact of flying by filling planes with “sustainable aviation fuel” (also known as SAF) from products such as used cooking oil and animal fat. Walking around the outdoor refinery was a strange experience – we had to wear head-to-toe protective gear including helmets, goggles and earplugs. In fact the health and safety was so rigorous we had to send our clothing and shoe sizes in advance so we could be kitted out with the right-sized boots, trousers and jackets. Most sinister were the carbon monoxide detectors we had to wear in case of emergency. The idea of there being a gas leak or this place exploding suddenly felt like a very real risk. The sprawling structure took the form of a dystopian hissing exoskeleton with a tangle of pipes and imposing tanks. A nearby coal factory belched black smoke into the air. Was it possible that this place was creating a product so revolutionary it could transform the carbon impact of flying? It often strikes me as somewhat hypocritical that the general public – and the media – are so quick to criticise the use of private jets, given that they only produce 4 per cent of aviation emissions. However, the resentment comes from the fact that the world’s wealthiest people – the 1 per cent – are collectively responsible for 50 per cent of global aviation emissions and many of them will be frequent private jet users. Their personal carbon footprints (a concept invented by BP, ironically) are far greater than the average person’s, and when compared to a regular airliner, private jets are up to 20 times more polluting, on a per passenger basis. If the 1 per cent can neutralise their aviation impact, then the world will be half way there. What’s more, trade body IATA believes that “sustainable aviation fuel” (SAF) could be the single-biggest contributor to helping the aviation industry achieve net zero by 2050.

It often strikes me as somewhat hypocritical that the general public – and the media – are so quick to criticise the use of private jets, given that they only produce 4 per cent of aviation emissions. However, the resentment comes from the fact that the world’s wealthiest people – the 1 per cent – are collectively responsible for 50 per cent of global aviation emissions and many of them will be frequent private jet users. Their personal carbon footprints (a concept invented by BP, ironically) are far greater than the average person’s, and when compared to a regular airliner, private jets are up to 20 times more polluting, on a per passenger basis. If the 1 per cent can neutralise their aviation impact, then the world will be half way there. What’s more, trade body IATA believes that “sustainable aviation fuel” (SAF) could be the single-biggest contributor to helping the aviation industry achieve net zero by 2050.

But how do we know it’s not just hype, in the way carbon offsetting seems to be (some experts say that carbon offsets are a scam)? In 2019, Victor decided to pay to 200 per cent carbon offset all its private jet flights on behalf of customers. But since January 2023, it has stopped. Four years ago, the decision was seen as revolutionary and progressive but now Victor has ditched this strategy in favour of an “industry-leading” partnership with Neste – its SAF promises to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 80 per cent over their lifecycle, compared with fossil fuels. Last year, Neste claimed its biofuel helped customers reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally by 11 million tons – the equivalent of the annual carbon footprint of 1.8 million EU citizens. Matti Lehmus, president and CEO of Neste, said in statement: “We are on track towards reaching our commitment of helping our customers to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20 million tons of CO2e annually by 2030.” Although SAF is a new technology it is already in production and being pumped on to planes around the world. It works but it is expensive, and its favourable carbon footprint is only maintained when it is not driven or shipped great distances. (The best option for distribution is via electric vehicle.) By 2030, many commercial airlines such as British Airways and Virgin Atlantic have committed to using a 10 per cent blend of SAF but the benefit of that will be relatively minimal, especially considering the anticipated growth of global aviation.

Matti Lehmus, president and CEO of Neste, said in statement: “We are on track towards reaching our commitment of helping our customers to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20 million tons of CO2e annually by 2030.” Although SAF is a new technology it is already in production and being pumped on to planes around the world. It works but it is expensive, and its favourable carbon footprint is only maintained when it is not driven or shipped great distances. (The best option for distribution is via electric vehicle.) By 2030, many commercial airlines such as British Airways and Virgin Atlantic have committed to using a 10 per cent blend of SAF but the benefit of that will be relatively minimal, especially considering the anticipated growth of global aviation.

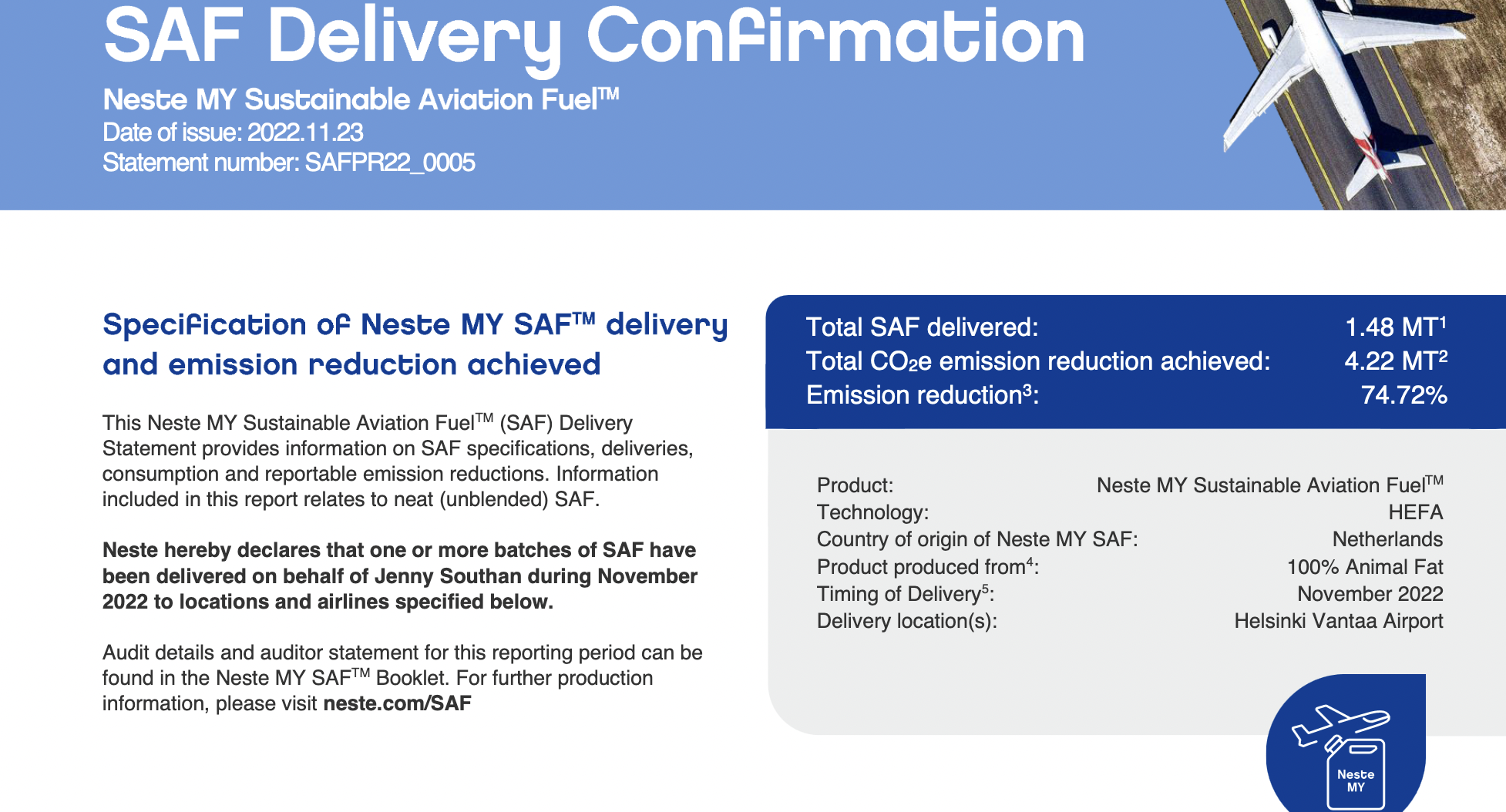

Since June 2022, Victor users have been able to buy SAF for their private jet flights, as well as credibly track their emissions savings. Upon boarding our aircraft at Biggin Hill, we were told that the fossil fuel for our flight was effectively replaced with 100 per cent SAF. However, the biofuel wasn’t actually pumped on to our plane – it was pumped on to a Finnair plane at Helsinki airport (Victor calls this approach “buy here, use there”). Obviously this can be pretty confusing so to prove that it powered a real flight, we were given a SAF delivery confirmation certificate, which showed that 1.48 metric tonnes of SAF (in this case made from animal fat) was delivered to Finnair, and it offered an overall emission reduction of almost 75 per cent on our flight. Is this really better than carbon offsetting? Not so long ago Victor proudly announced that in the first six months of the campaign, it had offset more than 25,000 tonnes of CO2e emissions via carbon offsetting – the equivalent of protecting tree cover nine times the size of New York’s Central Park, via nature-based carbon reduction and sequestration projects such as the Ningxia Shapotou Hydropower Project in China. By 2022 Victor said it has offset 148,680 tonnes of CO2. In a change of tact, instead of offsetting on behalf of all passengers, the charter company placed the responsibility back on the customer, by inviting them to pay for a certain percentage of SAF (from 5% to 100%) to offset a portion of the emissions from their flight instead.

Is this really better than carbon offsetting? Not so long ago Victor proudly announced that in the first six months of the campaign, it had offset more than 25,000 tonnes of CO2e emissions via carbon offsetting – the equivalent of protecting tree cover nine times the size of New York’s Central Park, via nature-based carbon reduction and sequestration projects such as the Ningxia Shapotou Hydropower Project in China. By 2022 Victor said it has offset 148,680 tonnes of CO2. In a change of tact, instead of offsetting on behalf of all passengers, the charter company placed the responsibility back on the customer, by inviting them to pay for a certain percentage of SAF (from 5% to 100%) to offset a portion of the emissions from their flight instead.

With pricing on a sliding scale, it costs about €675 to offset one tonne of CO2 with SAF. So how much did it cost to offset our flight to Rotterdam? We were flying a return trip aboard a Legacy 650 heavy jet, which cost €25,250 plus €3,520 for the SAF – 14 per cent more expensive than regular jet fuel, Neste told us. What’s uptake been like – are people willing to pay the extra? In November 2022, when we did our trip, Victor said that it had received 111 booking requests for SAF representing about one in five (or 20 per cent) of jet charters (remember that private jet users aren’t just celebrities, they are government officials, medical professionals, company CEOs and so on). Most clients choose about 30 per cent SAF for their trip. (Here’s me looking happy about our 100 per cent SAF flight.) In an open letter, Victor CEOs Toby Edwards and James Farley jointly stated: “We have been able to demonstrate the existence of a motivated cohort of customers who are willing to match or better our commitment and pay a significant premium to fly with Sustainable Aviation Fuel on their charter flights. We believe those most able should help to shoulder the responsibility for their lifestyle choices and that we all have a responsibility to make a difference. Reducing emissions by chartering more fuel-efficient private jets, coupled with purchasing SAF as a replacement to fossil fuel, now offers the clearest path to achieve net zero.”

In an open letter, Victor CEOs Toby Edwards and James Farley jointly stated: “We have been able to demonstrate the existence of a motivated cohort of customers who are willing to match or better our commitment and pay a significant premium to fly with Sustainable Aviation Fuel on their charter flights. We believe those most able should help to shoulder the responsibility for their lifestyle choices and that we all have a responsibility to make a difference. Reducing emissions by chartering more fuel-efficient private jets, coupled with purchasing SAF as a replacement to fossil fuel, now offers the clearest path to achieve net zero.”

Flying back on our private jet in the evening, with a glass of champagne in hand, I couldn’t help but wonder if SAF was as benevolent as it seemed. Given SAF burns in the same way as normal fossil fuel, it still emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The “offset” comes from the fact that the production of it is less damaging than drilling and refining oil. The fact that Neste upcycles used cooking oil from McDonald’s, and is also exploring developing SAF from other “feedstocks” such as algae and municipal solid waste, then that has got to be better. The reality is that it is early days – right now, SAF only accounts for about 0.1 per cent of all aviation fuel burnt. But Neste is betting big, with work already underway to expand its Rotterdam refinery at a cost of €1.9 billion by 2026, making it one of the largest SAF production facilities on the planet. It also has a SAF refinery in Singapore. Is it just greenwashing? Many people will argue that using SAF as a way of justifying private jet travel – or just more air travel in general – is indeed greenwashing. The fact is, the pollution is still going into the atmosphere. And there are also problems with where some SAF comes from (in the past some companies have used palm oil). According to Greenpeace, six out of seven of Europe’s biggest commercial European airline groups either rely on SAF, or plan to use it to tackle emissions, but none has “explicitly excluded the use of harmful agrofuels which are linked with environmental destruction, deforestation, human rights abuses and food shortages”. Greenpeace says that European airlines “overemphasise the use of SAF as a tactic to appear green when in fact this accounted for as little as 0.1% or less of the total annual jet fuel consumption of any airline analysed in 2019”.

Is it just greenwashing? Many people will argue that using SAF as a way of justifying private jet travel – or just more air travel in general – is indeed greenwashing. The fact is, the pollution is still going into the atmosphere. And there are also problems with where some SAF comes from (in the past some companies have used palm oil). According to Greenpeace, six out of seven of Europe’s biggest commercial European airline groups either rely on SAF, or plan to use it to tackle emissions, but none has “explicitly excluded the use of harmful agrofuels which are linked with environmental destruction, deforestation, human rights abuses and food shortages”. Greenpeace says that European airlines “overemphasise the use of SAF as a tactic to appear green when in fact this accounted for as little as 0.1% or less of the total annual jet fuel consumption of any airline analysed in 2019”.

However, Globetrender is always an advocate of innovation and SAF holds great potential for an era beyond fossil fuel. In the future, it is hoped that flights will be powered by 100 per cent SAF but at the moment regulations allow for a 50 per cent blend. Widespread use won’t occur, though, until government mandates are introduced, production becomes far more plentiful and costs come down significantly. There has also got to be trust from consumers, too – but imploring the general public to pay extra for SAF on commercial flights is not the route to go down. Airlines need to do it as standard and pass on the cost in the form of higher ticket prices, if needs be. (I’d like to see Victor do this for private jet charters.) Until then, it will be down to responsible private jet users (if that is not a paradox) to lead the way.